Reposted from 2009

1

‘Ah,’ he said, ‘Count Magnus, there you are. I should dearly like to see you.’

‘Like many solitary men,’ he writes, ‘I have a habit of talking to myself aloud; and, unlike some of the Greek and Latin particles, I do not expect an answer. Certainly, and perhaps fortunately in this case, there was neither voice nor any that regarded: only the woman who, I suppose, was cleaning up the church, dropped some metallic object on the floor, whose clang startled me.’

Despite their capacity to create mortal fear, the presentation of ghosts must be delicately handled. They are sensitive entities, with a particular aversion to being overdescribed, which leads many of them to avoid the light. We must tread carefully, so that we don’t frighten them.

MR James was a masterly handler of ghosts, an aspect of which is his skilful management of framing devices.

In The Mezzotint the narrative of horror takes place within the frame of the picture, and Dennistoun’s first sighting of the demon in Canon Alberic’s Scrapbook is in a lurid picture of it at the court of Solomon, in the scrapbook of the title (‘One remark is universally made by those to whom I have shown the picture: ‘It was drawn from the life.”).

The practice is not, of course, limited to actual pictures – that would be tediously unvarying and unimaginative – but extends itself across, among others, dolls houses, Punch and Judy shows (the wonderful, unregarded Story of a Disappearance and an Appearance), mazes and, naturally, dreams. Nested narratives of letters, diaries, travelogues and gossip also provide suitable settings for horrific apparition.

These are frequently the places where the initial stages of the ghost’s appearance occur, the way it first insinuates itself into the physical world. It is also the place where the ghost is most willing to show itself in its true form: ghosts in his stories are at their most vivid when they are furthest from the real world of the reader. They fragment the closer they approach us, to the point of imminence where they may be represented by just a claw, a mouth, a series of panicked or uncertain glimpses.

One of the effects of the framing device is to engage our belief: disbelief in what the picture frame contains does not affect our belief in the existence of the picture itself; we may not believe in fairies, but we believe in fairy stories; we should be surprised by the appearance of a vampire in our local pub, but we should not be surprised by the appearance of a vampire movie at our local cinema. At least this is what we naively believe – but the rules of the ghost story are the rules of the supernatural, and every ghost story writer knows what every ghost knows: frames aren’t containers, they are portals.

‘And then if you please, he switched on another slide, which showed a great mass of snakes, centipedes, and disgusting creatures with wings, and somehow or other he made it seems as if they were climbing out of the picture and getting in amongst the audience.

In fact the reader shares the characteristics of James’ academics, willed curiosity and innocent scepticism. We desire to read the story (willed curiosity), and we approach it as a story (innocent scepticism) but we should perhaps be more cautious, lest sharing these characteristics should lead us to share their fate – only one story, The Tractate Middoth, has anything like a happy ending.

In Count Magnus there are numerous frames, pictures within pictures, tales within tales.

The first voice is that of the antiquary narrator, who has come into possession of some papers by a Mr Wraxall, the second voice.

Mr Wraxall has gone on a tour of Sweden, and has stopped in the town of Råbäck, where is carrying out researches for a possible book. Here he encounters the history of Count Magnus, nearly three centuries dead, who went on a mysterious Black Pilgrimage to the city of Chorazin.

On making enquiries, the reluctant landlord of the inn that Wraxall is staying at agrees to tell him a tale that his grandfather told him, this is the third voice. We are now at three narrative removes from the room of the antiquary where we started, a picture within a picture within a picture. The tale he is told is of two men going to hunt at night in the recently dead Count’s forest, and, on their failure to return, the search for them the next morning –

“I heard one cry in the night, and I heard one laugh afterwards. If I cannot forget that , I shall not be able to sleep again.

‘So they went to the wood, and they found these men on the edge of the wood. Hans Thorbjorn was standing with his back against a tree, and all the time he was pushing with his hands – pushing something away from him which was not there. So he was not dead. And they lead him away, and took him to the house at Nykjoping, and he died before the winter; but he went on pushing with his hands. Also Anders Bjornsen was there; but he was dead. And I tell you this about Anders Bjornsen, that he was once a beautiful man, but now his face was not there, because the flesh of it was sucked away off the bones. You understand that?’

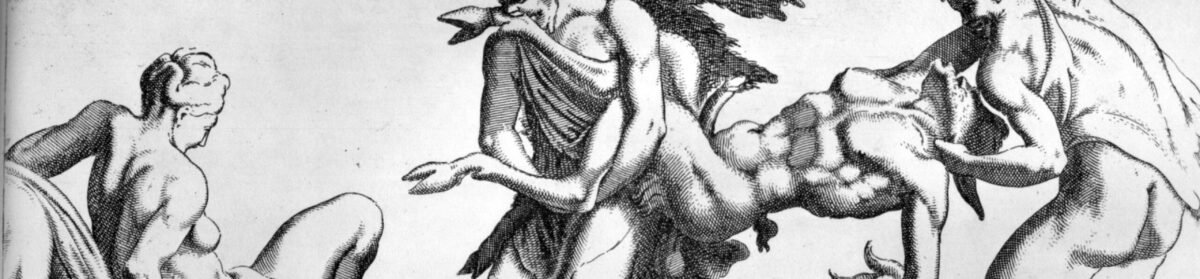

The next day Wraxall goes to the church and enters the mausoleum and finds the copper sarcophagus where the Count is buried, which has, round the edge, several engraved bands, ‘representing various scenes.’

One was a battle, with cannon belching out smoke, and walled towns, and troops of pikemen. Another showed an execution. In a third, among trees, was a man running at full speed, with flying hair and outstretched hands. After him followed a strange form; it would be hard to say whether the artist had intended it for a man, and was unable to give the requisite similitude, or whether it was intentionally made as monstrous as it looked. In view of the skill with which the rest of the drawing was done, Mr Wraxall felt inclined to adopt the latter idea. The figure was unduly short, and was for the most part muffled in a hooded garment which swept the ground. The only part of the form which projected from that shelter was not shaped like any hand or arm. Mr Wraxall compares it to the tentacle of a devil-fish, and continues: ‘On seeing this, I said to myself, “This, then, which is evidently an allegorical representation of some kind – a fiend pursuing a hunted soul – may be the origin of the Count Magnus and his mysterious companion. Let us see how the huntsman is pictured: doubtless it will be a demon blowing on his horn.” But, as it turned out, there was no such sensational figure, only the semblance of a cloaked man on a hillock, who stood leaning on a stick, and watching the hunt with an interest which the engraver had tried to express in his attitude.

Once again, the most vivid images of horrific implication are deeply interred within the story, presented in a picture within a picture within a picture, like the triple padlocks that seal Count Magnus’s sarcophagus, although – Wraxall notes on his first visit – one has come asunder and lies on the floor…

2

Tonight, for the second time, I had entirely failed to notice where I was going (I had planned a private visit to the tomb-house to copy the epitaphs), when I suddenly, as it were, awoke to consciousness, and found myself (as before) turning in at the churchyard gate, and, I believe, singing or chanting some such words as, “Are you awake, Count Magnus? Are you asleep, Count Magnus?” and then something more which I have failed to recollect. It seemed to me that I must have been behaving in this nonsensical way for some time.’

[…]

‘I must have been wrong,’ he writes, ‘in saying that one of the padlocks of my Count’s sarcophagus was unfastened; I see tonight that two are loose.’

Advertisements

Report this adPrivacy

I said that ghosts do not like the light. This is because, although they have a fondness for apparition and animation, they do not like being seen. The eye is the sense organ of light, and is the vehicle of that reason that comes from observation, which we call science, and is the symbol of the movement that promotes that reason, the Enlightenment.

Ghosts never appear in well-lit laboratories, are notoriously chary of experimental conditions, in the light of science they become ‘phenomena’, their trappings bed sheets, paste-board masks, projections of psychological megrims and disorder. They may look unconvincing or gimcrack, even becoming subjects not of fear but (disastrously for their ability to frighten) of mockery, laughter and scorn.

The eye is also the most sedulously duplicitous of the sense organs, its world so detailed and convincing, so seemingly incapable of modification, that we call its representations reality. This is the world we exist in, and its light is the light by which we read. In order to have a successful ghost story, the ineluctable modality of the visual must be eluded, the rules of reason modified.

Or you can do what Rudyard Kipling did in The End of the Passage – take the very instruments of observational rationalism, the camera and the eye, and make them the vessels of the terror that they are supposed to dissolve, producing an ocular ghost story.

‘T’isn’t in medical science.’

‘What?’

‘Things in a dead man’s eye.’

The End of the Passage – Rudyard Kipling

Only a writer of Kipling’s genius could do this. He has the short-story writer’s knack of economy – suggesting experience and knowledge beyond what is described on the page.

His expertise in this area was honed by his early newspaper writing. His early stories, collected in Plain Tales from the Hills, inferred entire tales from scraps of society gossip, snatched market overhearings, cryptic glimpses of everyday Anglo-Indian life, and fitted them to a column-and-a-half of newsprint.

In a sense, The End of the Passage isn’t a ghost story at all – the only apparition is of someone still living;

Hummil turned on his heel to face the echoing desolation of his bungalow, and the first thing he saw standing in the verandah was the figure of himself.

Kipling implies (without ever describing or explaining) what Hummil sees in his mind, or I should say what he sees in his eye. A terrifying supernatural force is suggested without ever being described, in fact it is sealed within the organ of description itself.

The background is a cholera epidemic – and in a wonderful opening (he was superb at atmospherics) Kipling sets the scene –

Four men, each entitled to ‘life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.’ sat at a table playing whist. The thermometer marked – for them – one hundred and one degrees of heat. The room was darkened till it was only just possible to distinguish the pips of the cards and the very white faces of the players. A tattered, rotten punkah of whitewashed calico was puddling the hot air and whining dolefully at each stroke. Outside lay gloom of a November day in London. There was neither sky, sun, nor horizon, – nothing but a brown purple haze of heat. It was as though the earth were dying of apoplexy.

Despite being an expert at the framing device (think of The Man Who Would Be King, or The Disturber of the Traffic) Kipling uses none here. Possibly because, as he suggests at the beginning of another excellent supernatural story The Mark of the Beast,

East of Suez, some hold, the direct control of Providence ceases; Man being there handed over to the power of the Gods and Devils of Asia, and the Church of England Providence only exercising an occasional and modified supervision in the case of Englishmen.

Advertisements

Report this adPrivacy

The laws that govern spirits of the West do not hold true for the East. He has also, as can be seen in the opening paragraph, already cut the four men off from the light and laws of the outer world.

After the whist party has broken up, one of the group, Hummil, confesses to another, a doctor, Spurstow, that he is losing his mind. Spurstow medicates him with morphine, which seems to help, and goes to attend to an outbreak of cholera in another district. That is the point at which Hummil turns to see the apparition of himself.

When they come back the following week they find Hummil in his bed.

The body lay on its back, hands clinched by the side, as Spurstow had seen it lying seven nights previously. In the staring eyes was written terror beyond the expression of any pen.

Spurstow asks another of the men, Mottram, to look into Hummil’s eyes.

Mottram leaned over his shoulder and looked intently.

‘I see nothing except some gray blurs in the pupil. There can be nothing there, you know.’

Despite Mottram’s insistence, Spurstow decides to take a photograph of the eyes with a Kodak camera, but destroys the pictures without showing them to anyone else.

‘It was impossible, of course. You needn’t look, Mottram. I’ve torn up the films. There was nothing there. It was impossible.’

‘That,’ said Lowndes, very distinctly, watching the shaking hand striving to relight the pipe, ‘is a damned lie.’

The eye is no longer the vessel of reason, and has become like the sarcophagus that contains Count Magnus, a vessel of mortal fear, unopenable, and sealed by more than padlocks.

3

‘You may have been a bit of a rascal in your time, Magnus,’ he was saying, ‘but for all that I should like to see you, or, rather -‘

‘Just at that instant,’ he says, ‘I felt a blow on my foot. Hastily enough I drew it back, and something fell on the pavement with a clash…’

Although Denton Welch was not a ghost story writer, there is often a tang of the macabre about his writing, sometime more than a tang. Take this paragraph from a description of a night time walk in his masterpiece A Voice Through A Cloud –

After a few minutes I was able to force myself on; but now the landscape seemed to be taking on an ugly significance. I imagined that the vacant plots between the raw gardens and houses had probably been left desolate in superstitious fear, because of vile crimes committed there. Perhaps in the moonlight, over and over again, night after night, a little child’s atrocious murder would be re-enacted; or there would be ghost figures loping over the ground, arms outstretched greedily, white hair on the palms of the brown-pink hands. Their fingers would be webbed. Yellow fangs, hollow and rotten, would jut from their dripping jaws, and eyes, on fire with hate and lust, would be swimming and swirling as my head was swirling.

He did write, however one short story, called Ghosts (collected in A Last Sheaf) which is an ingenious variation on the technique of gradual revelation through multiple narratives. It consists of three supernatural experiences, each very different from the other.

The first is a description of a ghost story he wrote at school, which has Welch’s characteristic level of fetishized detail –

I panelled my imaginary room in pine and finished it with a heavy cornice. From a cracked punch-bowl came the faint scent of mildewed rose-leaves, and a hissing fire of green branches spat and danced on the scratched marble heath [sic – hearth?]. The hangings of the fantastically high bed were of rose madder damask, faded in parts to tawny, dried-blood colour, and they were so rotten that they had to be held together on a new foundation by countless lines of cross-sewing.

Advertisements

Report this adPrivacy

The ghost that appears to him in the middle of the night is ‘a beautiful woman, tall and sweeping and not young – ageless, like the queens in fairy tales.’

The story is read out in class, and goes down well, until the teacher gets to a phrase that Welch has taken from the Bible – ‘the hair of my flesh stood up.’ His schoolmates are not charitable:

Instantly laughter broke out all over the room and voices called out: “Oh, I say, Welch, do they really stand up?” “Oh Welch!”

Unwisely rushing to my own defence as a writer by referring them to my august source, I protested: ‘But it’s in the Bible! You can read it there.”

This started a second storm of laughter, groans and mockeries. I thought: “Let them laugh. Everything is ridiculous if you like to make it so.”

He remembers this first story when a second story is told him, while a guest at a friend’s house in Sussex. He is sitting shelling peas on a summer’s evening with another guest, a woman, who tells him of her visit to a large old house in the Midlands, where a remarkable ghost appears to her in the night –

…she was woken, just as I had been in my story; although it was not a beautiful woman that she saw, but a huge filmy egg, made out of mucus membrane and lighted from within. It floated slowly through the darkness until it was above her in the bed. She saw with horror then that the egg-shaped glow encased the face and shoulders of a man. The shoulders were naked and just below them the body dissolved into stringy, phosphorescent mucus. Round his head was a squirming halo of the same. The flesh was of an extraordinary ruddiness, and exaggeratedly tight, as if the image had been blown up with a bicycle-pump.

The young man was grinning at her, showing his white, animal teeth. On his forehead were hot brown curls and the needle points of his eyes bored into her.

Fascinated, she watched until it disappeared on the other side of the bed, then she lay still, wondering what it could be, until, most surprisingly, she fell asleep again.

The next morning she tells her hosts about the apparition and is told that ‘the image appeared in various parts of the house, not only in that room.’

Sometimes it sailed down the passages. The face and the shoulders were all that could ever be seen. They had no explanation to give for the appearance of the image, except a rather unconvincing tradition about a young man, a villain, and an ancestor of theirs.

Although as a whole Welch’s story is somewhat inconsequential at this stage, the way he has moved from the description of a conscious fiction at the beginning to a more documentary tale, all related in his typical unfeigned autobiographical voice, represents a novel, perhaps even counter-intuitive approach to the literary problem of conjuring ghosts.

A comparison of the two stories by Welch leads to an experience of intense revelation that retrospectively gives the whole story its force:

For a moment after the end of the story we went on shelling peas in silence. The pods, as they were ripped open, made a sucking noise, like mouths gasping for air. My mind was busy comparing the true experience with my invented one. I could think of nothing but ghosts; I was filled with the idea of them.

And jumping up restlessly, I left my companion, and the empty pods on the lawn; and I wandered a long way until I came to a black pool almost surrounded by tangled thickets. I knelt down and dipped my hand in the still water. My fingers were magnified into fat, curling grubs. Baring my arm, I stretched down till I felt rotting branches and twigs soft as horse’s noses. I pulled, and a mossy, peeling antler rose dripping from the pond. Delving still deeper I came to a pile of excrement and leaves, layer on layer, and limp and black as chow dogs’ tongues.

It was evening now, with the sun setting. I looked up at the turquoise sky, then down at the stirred-up water where black motes like pepper starred the pinkness of my tingling arm. From across the pool a dull blind window suddenly flashed back the dying fire of the sun, and a rush of birds streamed out above me. I saw the woodman’s ruined shelter of branches, and his pile of bark peelings turned now into a mass of dead mottled snakes.

Everything at that moment held a secret. Everything was haunted. But human eyes were not the right eyes, and my ears would never hear.

Advertisements

Report this adPrivacy

The three varied narratives are three keys to three padlocks, the unlocking of which brings about a sense of the imminent revelation of places and beings not normally seen by living eyes, here, in the lighted world.

…It was the third, the last of the three padlocks which had fastened the sarcophagus. I stooped to pick it up, and – Heaven is my witness that I am writing only the bare truth – before I had raised myself there was a sound of metal hinges creaking, and I distinctly saw the lid shifting upwards. I may have behaved like a coward, but I could not for my life stay for one moment. I was outside that dreadful building in less time than I can write – almost as quickly as I could have said – the words; and what frightens me yet more, I could not turn the key in the lock. As I sit here in my room noting these facts, I ask myself (it was not twenty minutes ago) whether that noise of creaking metal continued, and I cannot tell whether it did or not. I only know that there was something more than I have written that alarmed me, but whether it was sound or sight I am not able to remember. What is this that I have done?’

October 31st, 2009

There is a wonderful project over at Freaky Trigger – ongoing discussions of MR James’ stories, well worth taking a look at.

Ghosts and Scholars collects a lot of material in one place to do with MR James.

One thought on “MR James, R Kipling, D Welch – Three Ghost Stories for All Hallows’ Even”